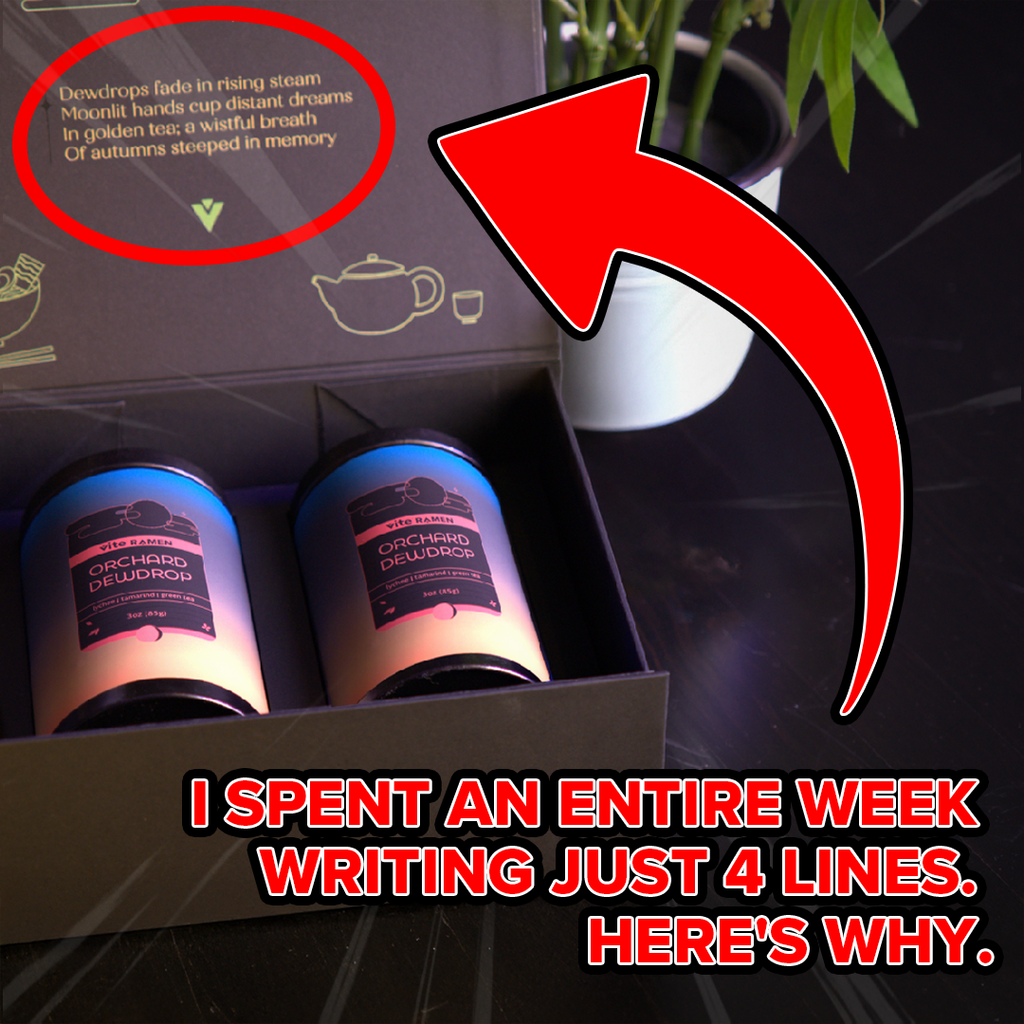

Welcome to the Vite Mid-Autumn Festival Tea

Read the tea on why Tim spent a week to write 4 lines nobody would read!

One hour left, and I wasn’t done. Pings kept going off on my other screen, flooding my notifications.

“Are you done yet?”

“Tim we need it now”

“Just send it no one’s going to read it anyway”

I stared at the glowing white document in front of me. I’d spent a week on this. An entire week...

And I only had 4 lines to show for it.

And I was stuck on picking "Dewdrops" vs "Raindrops" vs "Teardrops."

This was a terrible business decision, I knew. But I was going to do it anyway.

Let me back up. August 12, 2024, a week before that incident, was the day it all started. It was supposed to be simple at first. Easy, even.

Our designer though it’d be neat to have a poem on the inside of our tea set box, something we were making for the Mid-Autumn Festival, and me, being the resident wordsmith (aside from all the other things I do), was pinged to write something for it.

“Just something simple,” they’d said, “Maybe like a haiku or something.”

Subject matter: tea, moon, autumn. Warmth, golden moon, that sort of stuff.

Sure, I can write a poem. Easy. This’ll take no time at all.

I cracked my neck, opened up a new document, and began to--

Wait. Hang on.

“Haiku are japanese,” I said, “And... we’re doing a distinctly Chinese Mid-Autumn Festival thing. Shouldn’t I do something else?”

“I just wanted it to be a poem that had the nature vibes.”

“Ah, okay. I can do whatever then. Much easier.”

A pause. I’m sure they knew what I was thinking already, and responded before I could start.

“Traditionally Chinese poetry would be... even worse. It doesn’t carry over to English well since it’s so syllabic,” they warned.

Damn. Caught red handed.

“Yeah, I know.”

Another pause. I could imagine them sighing on the other side of the screen.

“You’re going to do it anyway, aren’t you?”

“...Yup.”

I can speak Chinese, born with it, grew up hearing it.

But, like many other asian americans, I can’t read or write, which also means I can't read classical poetry.

I’d never really learned this part of my heritage, as much as I’d explored some of the more fun parts like Three Kingdoms and food and the like. This kind of thing was more... esoteric, academic, the kind of thing that, when I asked my parents about, even they shook their heads in dismay at how difficult it was.

They’d never done anything like it either.

But hey, I’ve trained and practiced just about every form of English poetry. Find a form of famous Chinese poetry, transliterate its form into English, like how you can do haiku in English.

Really, how hard could it be?

...WELL.

Mid-Autumn Festival is traditionally about reunion. Families gathering under the full moon, sharing mooncakes, celebrating harvest-- Chinese Thanksgiving of sorts, you could say.

The importance in traditional Chinese culture can’t be understated, but for those of us who grew up in the west, it’s something that’s a little more removed. Something that we perform, go through the motions of, but... might not really feel the same importance for. It’s a holiday that can easily get forgotten and overlooked.

While it’s generally expected for people to travel for Lunar New Year, many asian americans might skip out on travelling for this holiday to see family, even though that might be an expectation in the traditional country.

Poems, in my opinion, should mean something, and say something.

Their form is unique so that they can express emotion and feeling in a way that longer forms of writing, like prose, can’t. Their generally shorter form allows for more resonant feeling per word, stuffing all of that emotion into those few short words.

Worse for those of us who speak English, actually. One of the reasons why I was warned about trying to transliterate poetry forms into English was simple.

In Chinese, each syllable is a word, and there’s fewer “filler” words like “is, the, like, to,” etc, allowing for a richer, denser poem structure.

And even tougher is that Chinese poetry relies heavily on the tonal language itself for a kind of musicality in the poem. While in English, we also have this in the form of iambic meter and rhymes, Chinese brings this to a whole different level of difficulty and musicality of words, as rhymes and meter still exist within many poetic structures there, too.

One of the most famous poetic structures, and largely considered to be one of the hardest, is the 七言绝句, generally referred to in English as qijue, a form of 绝句(jueju).

Not to get TOO deep into this, but this is a quatrain, formed by a matched pair of couplets, seven characters per line.

Simpler to understand would be:

Two sets of rhyming lines.

Seven syllables per line.

So, of course, I decided to do the hardest one. But not due to some masochistic tendency that I’m sure a lot of you might think about me at this point, but because... it was different. Unique, as I researched what form I wanted to try writing.

Because see, I can’t read or write Chinese. Every single poem, every single word, I have to put into a translation app, and have it read out to me. Even then, the exotic, ancient Chinese can be hard to understand even for a native speaker, much less interpret for all the meaning that exists within the poem’s form itself.

And I’d gone through a couple different versions of Chinese poems, from 賦(Fu) to 古诗(Gu Shi), but...

But when I listened to this form...

独在异乡为异客,

每逢佳节倍思亲。

遥知兄弟登高处,

遍插茱萸少一人。

Alone in a foreign land as a stranger,

I miss my family doubly during the festivals.

I know from afar my brothers climb to high places,

Each wearing dogwood sprigs—but one person is missing.

It’s by Wang Wei (王维), a poet from the Tang Dynasty, 1,300 years ago.

More than a millenia has passed since he wrote it.

And yet, when I listened to the poem read out loud to me, travelling through the centuries by a mechanical, soulless voice...

I cried.

I couldn’t go back last year during the mid-autumn festival. I was too busy with Vite, with work, with everything that I was doing. My family sent pictures, of course. More than Wang Wei would’ve had, more than a thousand years ago, but I felt the ache all the same.

A thousand years gone, and I felt the same pain that he must’ve felt all those years ago.

床前明月光,

疑是地上霜。

举头望明月,

低头思故乡。

Before my bed, bright moonlight gleams,

I suspect it's frost upon the ground.

Raising my head, I gaze at the bright moon,

Lowering my head, I think of my hometown.

By Li Bai (李白)

A thousand years gone, and I saw the same moon that Li Bai would’ve seen, cast snowy white against the ground, reminding him of a home far away.

I’ve never thought of China as my home. Still don’t. I’m American, I speak English as my primary language. This was translated, losing some of the meaning, losing cultural context, losing so much, and yet...

The jeuju is special as a poetic form because of its musicality. The special way that it must be formed so that the words themselves, spoken with the tonal language that is Chinese, creates a melody in and of itself that makes the poem all the richer for it.

And when I heard these poems... That’s why I knew I had to write this.

There’s a certain irony to where I’m stopping in this story. I have so much more I want to talk about, from the connection to haiku that I found, to how brutal it was to write the poem itself, and transliterate meaning and form and the inherent musicality of it all.

I spent an entire week writing it, after all. But, I’m out of time.

For now? I’ll leave you with the poem to read, and interpret yourself. I’d love to hear what you have to think about it, and if you think I succeeded, or if it didn’t quite work.

Dewdrops fade in rising steam

Moonlit hands cup distant dreams

In golden tea; a wistful breath

Of autumns steeped in memory

I want to write more about this later, but...

Today? I’m stopping writing. Because this year, I don’t want to feel the wistful nature of those poems. I don’t want to feel the heartache.

This year, I don’t care what else is happening tonight.

Because across all of the thousands and millions of years we’ve existed, across the boundless miles that stretch across the earth, there is only these few decades that I get to spend with them.

And I would rather have happiness, than wistfulness.

I’m going to go see my family now, and I hope you, too, can see your loved ones.

If you’re interested in the teas and teacups we made, we have them in a limited quantity for this year.

You can get yours here!

Remember to be kind, and savor life’s little victories... and treasure those moments that you can spend with your loved ones.

I know I will.

-Tim, CEO/Founder Vite